Advertisement

Microplastic Pollution

Tiny plastic beads create a very big problem

Used in everything from cars to mobile phones, plastic has transformed our everyday lives. The stuff is everywhere, and it’s showing up in some places that may surprise you, such as toothpastes, body scrubs, deodorant, and even lip gloss.

Advertisement

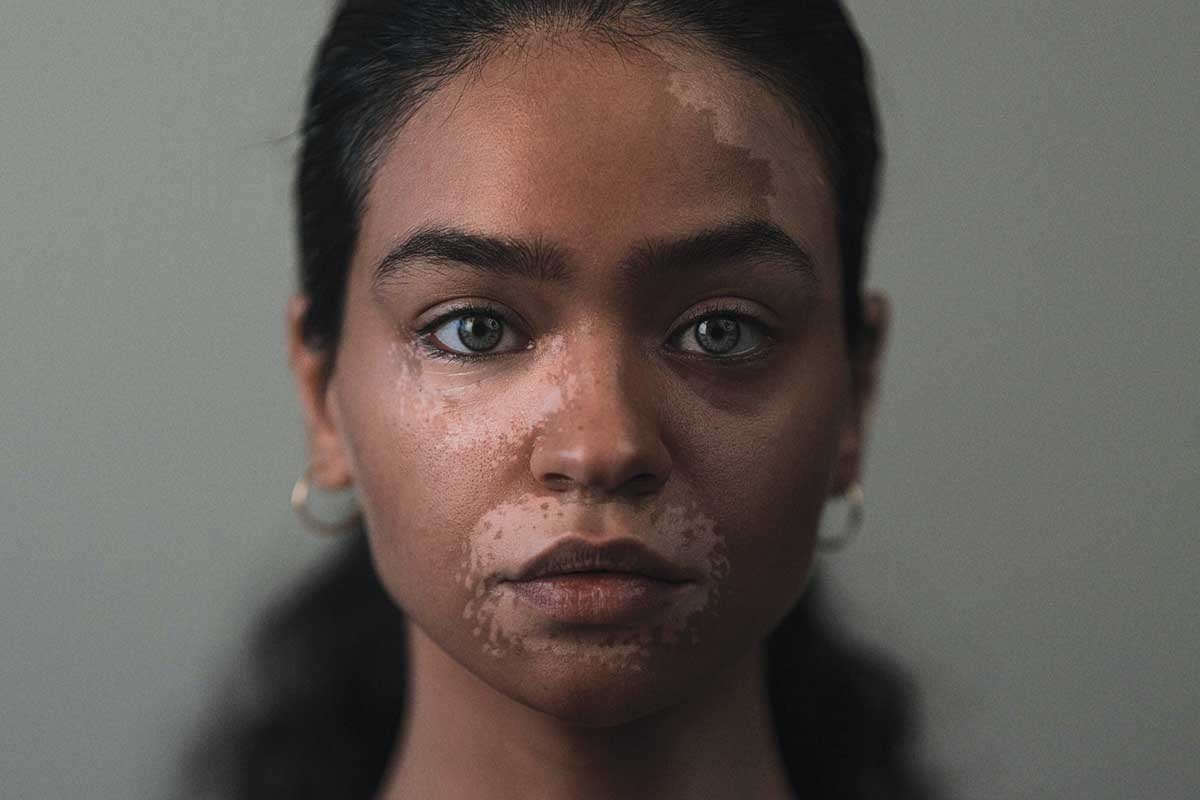

Microbeads in your toothpaste

Tiny pieces of plastic called microbeads are added to dozens of personal care products, supposedly to do things like make our teeth whiter and our skin smoother. They might be miniscule in size, but these plastic particles are having a major impact on wildlife, the environment, and, potentially, human health.

Advertisement

Microbeads down the drain

Microbeads, which also appear in some creams, soaps, shampoos, eye liner, sunscreens, and deodorants, are marketed by cosmetics companies as having an exfoliating quality. Usually less than one millimetre in diameter, microbeads are so small that water-treatment plants can’t filter them out, meaning they go straight from your bathroom sink or shower drain into the water supply.

Advertisement

Microbeads in the food chain

Research shows that microbeads are turning up in oceans and lakes and on shorelines. They aren’t biodegradable, so once they appear in the marine environment they’re impossible to remove. And they end up being eaten by fish, birds, and animals, working their way up the food chain. Since humans are at the top, people are likely also ingesting microplastics—and the toxins they accumulate—through the food we eat.

“People tend to think of [personal] cleaning products as healthy; they use them to clean their face and body, so it just doesn’t connect that there would be something nasty in there,” says Bill Wareham, western region science projects manager with the David Suzuki Foundation.

Adds Wareham, “Plankton, fish, and birds will see plastic microbeads and mistake them for food and ingest them. The chemicals release into the system of the animal and usually move into fat tissue—in fish, it’s the fatty layers that we eat—and this is where chemicals can accumulate.”

When living creatures consume microplastics, they’re fooled into thinking their bellies are full. Filter feeders such as mussels and clams are especially vulnerable. “It’s not real food, obviously, so they’re not getting any nutrition,” Wareham says. Those teeny bits of plastic can cause digestive blockages and dehydration as well as death from starvation, according to Environmental Defence.

Advertisement

Tiny toxic sponges

Making matters worse is the fact that the plastic fragments attract and act like sponges for other pollutants and chemicals, making them even more toxic to the marine life and birds that ingest them. They bio-magnify up the food chain, meaning the top predators, such as tuna and swordfish—types of seafood that often end up on people’s dinner plates—have the highest concentrations.

Advertisement

Microbeads are ubiquitous in our waterways

More and more research is looking at the prevalence of microbeads in the environment and their effects on wildlife and ecosystems.

In the Great Lakes

The nonprofit 5 Gyres organization has found an average of 43,000 beads per square kilometre in the Great Lakes, with concentrations averaging 466,000 near cities. Certain areas of the Great Lakes have concentrations as high as those in large oceanic gyres, according to a study published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research in March 2015. Among the Great Lakes, the highest concentration of microplastics is in Lake Erie.

According to the David Suzuki Foundation, tests on fish from Lake Erie found an average of 20 pieces of plastic in medium-sized fish. Cormorants, which eat fish, had an average of 44 pieces of plastic in them each.

Even more disturbing is that preliminary research has shown that some of the plastic debris collected from Lake Erie carries polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), both of which are capable of causing cancer and birth defects, according to the 2015 Journal of Great Lakes Research study.

In the St. Lawrence River

Scientists have also found microbeads at the bottom of the St. Lawrence River. In some spots, researchers measured more than 1,000 microbeads per litre of sediment, a magnitude that also rivals the world’s most contaminated ocean sediments, according to a study published last year in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences.

Advertisement

Turning the tide on microbeads

As environmentalists, scientists, and health-conscious Canadians learn more about microbeads, the tide is turning, with calls for change.

Earlier this year, New Democrat MP Megan Leslie introduced a motion in the House of Commons calling for microbeads to be added to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act’s list of toxic substances. This would effectively ban them from the market. The motion passed with unanimous support, though at press time, the motion hadn’t been acted on.

“There’s absolutely no need for microbeads,” Leslie tells alive. “It’s awful, awful stuff. We have a lot of research showing the impact on marine life and ecosystems, and there’s no reason to delay on taking action on this. We need compliance from all companies, which is why we need to regulate.”

Environment Canada has initiated a scientific review to assess the effects of microbeads on the environment.

In the US, Illinois and New York State banned the sale of cosmetics containing microbeads. Minnesota, Ohio, and California are also considering legislative action to prohibit the sale of products containing microbeads. Quebec’s Green Party wants the province to follow suit, and Toronto has called for a ban on the use of microbeads in personal care products.

Some manufacturers are taking positive action, removing microbeads from their products and in some cases replacing them with biodegradable alternatives. L’Oréal and Johnson & Johnson are two companies that are pledging to phase out microbeads from their products.

Advertisement

Ways to get involved

To eliminate the use of microbeads, 5 Gyres, a nonprofit environmental organization that “works to restore healthy, plastic-free oceans,” has a petition urging companies to replace microbeads with natural, nonharmful substances: 5gyres.org/microbeads.

Aside from not using products with microbeads, the David Suzuki Foundation’s Wareham also suggests writing to your MP to push for a nationwide ban on microbeads.

“We need public support,” he says. “Tell the government we don’t want our water bodies polluted with this plastic and we need to have industry regulated. People can have an effect by showing up with their voice, letters, and emails to government.”

Those messages can also be sent directly to cosmetics companies.

Advertisement

Natural alternatives to microbeads

Before plastic microbeads came along, there were plenty of healthy ways to get your skin to glow—and there still are.

Oatmeal, walnut shells, apricot seeds, powdered pecan shells, bamboo, baking soda, and sea salt are just some of them. They have the gritty texture that’s ideal for exfoliation.

“Another alternative is just to go back to using soap and a face cloth,” says Bill Wareham, western region science projects manager with the David Suzuki Foundation. “How novel is that? It’s about getting back to basics.”

Advertisement

Red flag ingredients

There are two key ingredients to watch out for when it comes to microbeads in personal care products: polyethylene and polypropylene. “If you see those on the label, then you know plastic microbeads are in that product,” says Bill Wareham of the David Suzuki Foundation.

Microbeads are also made out of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

Beat the Microbead: International Campaign Against Microbeads in Cosmetics has a list of products in Canada that contain the material, available for free download. Among items found containing the substances in a spot check earlier this year were Aveeno’s Skin Brighten Daily Scrub, Clearasil’s Daily Facal Scrub, and Neutrogena’s Oil-Free Acne Wash.