Advertisement

Marine Mystery

Jellyfish are taking over

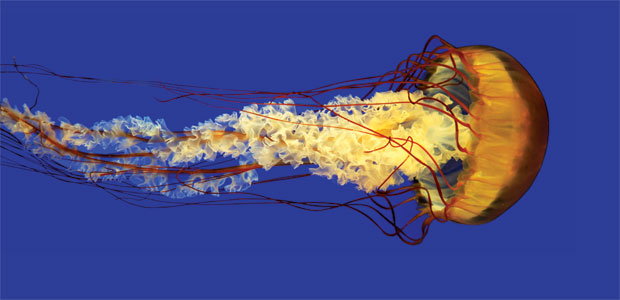

Thousands of poisonous, heartless, brainless creatures are taking over vast swaths of the world’s oceans. The boneless blobs might seem otherworldly, but they aren’t aliens–they’re jellyfish. In certain seas, their populations are exploding, and some scientists view the phenomenon as a sign of ecological disaster.

In the Bering Sea the jellyfish population increased more than tenfold in the 1990s, according to Claudia Mills, an independent research scientist out of the University of Washington. Similar spikes in numbers–known as “blooms”–have been documented in the Gulf of Maine, the Sea of Japan, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Mediterranean, as well as off the coasts of Alaska, Australia, Namibia, and Norway. Although jellyfish might seem harmless when they’re gracefully floating in an aquarium tank, they’re anything but when they show up in massive swarms in the ocean.

In Japan, for instance, blooms of Aurelia aurita medusae have caused temporary shutdowns of power plants, after the jellies clogged the systems’ intake screens. In Northern Ireland, a mass of mauve stinger jellyfish destroyed 120,000 salmon in a local fish farm. (Their sting can be deadly to young fish.) The massive jellyfish bloom was incredibly dense, with the gelatinous invertebrates forming a layer 10 metres deep.

Peaks of jellyfish masses aren’t new; populations often fluctuate seasonally. But the cycles between blooms seem to be getting shorter and the masses bigger and more widespread. No one knows exactly why the population explosions are happening. What is certain is that more people are becoming increasingly concerned about the health of marine ecosystems.

Canaries in the Coalmine

Many scientists insist we are dealing with troubled waters indeed. Mills says that jellyfish blooms occur in systems that are “out of balance.” Josep-María Gili, a research professor at the Barcelona-based Institute of Marine Sciences, says the recent growth in jellyfish numbers is a “message from the sea that something is wrong.”

It appears that jellies thrive in bodies of water that have been negatively affected by human activity.

Some researchers suspect that global warming has heated up oceans and triggered milder temperatures, not to mention fewer winter storms, which together create ideal breeding conditions for jellies.

Then there are industrial, agricultural, and urban factors. Agricultural runoff, for instance, can lead to the discharge of excess nutrients into bodies of water. High levels of nutrients provide ample nourishment for the organisms off which jellyfish survive.

Dennis Thoney, director of facility operations and animal management at the Vancouver Aquarium, concedes the blooms could be the result of eco-unfriendly practices.

“It’s possible, although we don’t know for sure, that population dynamics may be associated with human-caused factors such as overfishing,” Thoney tells alive in an interview. Fewer fish means less competition and more food such as plankton for jellies to consume. “Very few fisheries in North America are not overfished…We need to ensure that everything we do is sustainable, especially fisheries.”

The Slipperiest of Fish

If scientists don’t buy into the theory that jellyfish blooms are a sign of ecological malaise, then at the very least they’ll admit they’re stumped by an emerging marine mystery. But that doesn’t mean they’re not trying to figure it out. Last year, Australia hosted the second International Jellyfish Bloom Symposium, drawing scores of scientists from around the world.

According to Popular Science, jellyfish are among the least studied ocean species, partly because of the challenges of working with them. The creatures–which are relatives of anemones and coral, and can range in size from 5 centimetres to 60 metres–are hard to handle and often fall apart when caught in nets.

With the dearth of information surrounding jellyfish blooms–and their escalating prevalence–Thoney says the phenomenon needs urgent research.

“It certainly is a signal that we should be looking at this to determine what could be causing huge changes in ecological balance,” he says.