Advertisement

Treat Your Brain Well

Your life depends on it

If you can use an ATM machine, set your alarm clock and remember why you set it, write a cheque, go back to work after a coffee break, and remember to pick up groceries on the way home, then the chances are you don’t have a brain injury.

The things that you and I do almost without thinking can cause severe difficulty for those with traumatic brain injuries.

A heavy personal cost

Head injuries are the fourth leading cause of death for Canadians of all ages, and the leading cause of death for Canadians aged one to 44 years. Although the death rate from brain injury has declined in the past decade, 13,906 Canadians died as a result of their injuries in 2003. Sadly, the high death toll is only one devastating consequence of a traumatic brain injury.

Traumatic brain injury survivors may be faced with many disabilities, depending on the area of the brain affected: from short-term memory loss to the inability to walk—the challenges are often significant and devastating.

Remember me?

Typically, brain injury survivors—or survivors as they like to refer to themselves—lose their short-term memories to the point where they cannot remember the very things you and I take for granted.

Paradoxically, survivors often retain their long-term memories and thus can remember only too well how they used to be, what they could do before, and thereby recognize—but have difficulty coming to terms with—their limitations.

Quebec resident Ted Philips ran his own very successful construction business. Coming home late one night, he hit a patch of black ice. He wasn’t wearing his seatbelt and was thrown through the windshield. Normally a safety-focused man, he had jumped in his truck, been distracted by some papers that had fallen on the floor, and forgot to buckle up.

After his accident, Ted was unable to concentrate for any length of time and had increased anxiety, severe depression, and dreadful mood swings. His short-term memory was almost nonexistent and his long-term memory haunted him.

While the toll of his injuries was terrible for Ted, it was almost unbearable for his family. Eventually his wife left him, taking his two young daughters with her. Like so many survivors faced with seemingly impossible odds, Ted turned to alcohol to cope.

Sadly, this often happens to survivors of brain injury. In Ted’s case, with the dedication of a brain injury life-skills worker and a supreme effort on Ted’s part, he now works part-time, is at peace with himself, and is reconnecting with his family.

A brain injury is forever

It was once assumed that nerves could not regenerate themselves; therefore brain injuries were permanent. However, more recent science suggests otherwise. While survivors are unlikely to return to their pre-accident level of function, most can relearn enough to lead purposeful lives.

James Passmore crashed his motorcycle in 1987. His frontal lobe was damaged. With extensive life-skills coaching and a lot of hard work from James, he slowly learned to control his now-volatile emotions.

After several years of therapy, James recognizes when his emotions are getting out of control and he can now walk away rather than resorting to violence. Many brain injury survivors react with inappropriate emotion, and overcoming this problem is extremely difficult.

|

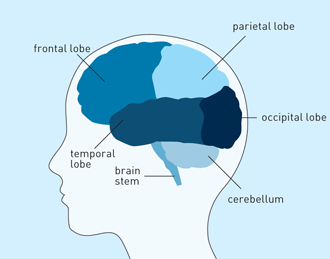

Although our brains are protected by a strong, bony skull, trauma to the brain can occur without major damage to the skull, because the brain can be smashed against the skull on the inside, as happens in many auto accidents. While some sensory areas appear to be specific to particular lobes, many of our control centres involve several areas of the brain. |

| Part of the brain | Areas involved | Injury symptoms |

| Frontal lobe | emotional control centre; motor function; problem-solving; memory; language; impulse control, social and sexual behaviour | memory loss; poor problem-solving abilities; loss of speech; impaired learning; emotional instability |

| Temporal lobe | smell; taste; perception; memory; musical ability; aggression; sexual behaviour; may contain language centre | loss of the senses of smell and taste; memory loss; inability to control aggression; inappropriate sexual behaviours; difficulty recalling words |

| Parietal lobe | the left lobe controls sensation and perception; the right interprets sensory input and integrates it with visual cues; understands where our bodies are in the physical environment; matches the written word with speech | difficulty in understanding left and right; poor writing and mathematical skills; diminished understanding of body and space; dramatically altered personalities; cognitive impairment |

| Occipital lobe | vision and perception lobes make sense of movement and recognize colours; allow us to understand shadows and colours so we can judge the distance and size of objects | hallucinations, illusions, and seizures; word blindness; writing impairment |

| Cerebellum | fine-tunes movement, balance, and equilibrium as well as muscle tone | uncoordinated movement, staggering, and swaying; muscle weakness; falls easily; slurred speech; abnormal, uncontrolled rapid movements |

| Brain stem | breathing; heart rate; swallowing | damage to this area usually results in death |

|

Prevention is the only cure According to the Canadian Brain Injury Association, the majority of brain injuries are preventable, so

|

The economic burden

Accurate information on the true economic burden of treating survivors of traumatic brain injury in Canada—and helping them return to society with meaningful lives—is difficult to come by. Most statistics come from the US and are extrapolated to Canada.

However, the SMARTRISK Foundation produces a paper, The Economic Burden of Injury in Canada, which looks at the estimated cost to Canadians of intentional and unintentional injuries. It states that in 2004 the cost was $19.8 billion. So obviously, the more we can do to prevent injury the better.

To that end, SMARTRISK and brain injury associations across Canada provide education and prevention workshops to schools, service clubs, and the general public. See sidebar, “Prevention is the only cure,” for some tips.

| The main causes of brain injuries | |

| Cause | Incident rate |

|

motor vehicle accidents |

45% |

| falls |

3% |

| assaults |

9% |

| other, including suicide attempts |

10% |

Real brains; real people

Unless we are personally touched by brain injury, we often know little about it—after all, brain injuries just don’t get the press that other diseases such as cancer or heart disease do.

Recently however, more information is being presented in the press about the risk of brain injuries, particularly in sports. The National Hockey League mandates helmets, and the American Football Association is considering changes to its rules to help prevent brain injuries.

The judiciary committee of the House of Representatives in the US met in January to assess the threat of brain injuries to players, particularly at school and college levels. As John Conyers, chairman of the committee, said, “Clearly, we have reached a tipping point in our understanding of the causes and treatment of brain injuries in football.” Let’s hope all sports reach that tipping point soon.

Yet, we must never forget that behind every statistic is a real person—along with their family and caregivers. Brain injury survivors are so much more than the sum of their injuries.

Jim Boulton’s car accident happened 20 years ago—he had been drinking at the time—and resulted in trauma to his cerebellum. Although Jim has now recovered enough to hold down a job and is a teetotaller and an avid skier, he still staggers when he walks and his speech is slurred.

As a result, he is regularly reported to the police because observers believe him drunk. Jim understands why this happens, but he wishes people would take a minute to talk to him, then they would realize he isn’t drunk at all; he is a brain injury survivor.

| Naturally brainy

Dr. Alan Logan, author of The Brain Diet (Cumberland House, 2006), insists that those suffering from a brain injury need a healthy diet, perhaps even more so than do uninjured people. “The research is making it clear that nutrition can influence the generation of specific nerve growth factors which are responsible for repair, growth, and maintenance of nerve cells,” he notes. The foods most recommended for survivors include the anti-inflammatory foods—deeply coloured fruits and vegetables, green tea, and seafood. Culinary herbs and spices such as turmeric also get the thumbs-up.

|

||||||||||||

Brain facts

The brain is divided into two distinct halves:

| Left side | Right side |

| controls the right side of the body | control centres for speech, logic, and cognitive functioning |

| controls the left side of the body | controls mathematical ability and thinks three-dimensionally |

Our brains—more than the sum of the parts

Our brains—more than the sum of the parts