Advertisement

More than Skin Deep

The psychology under the surface of skin care

Fact-Checked

This article has been written and fact-checked by experts in the field.

The skin is the body’s largest organ and the meeting place between our external and internal worlds. The relationship between stress and skin conditions has been documented since ancient times; however, the causal or aggravating link between stress and skin conditions has only been studied for the last few decades.

Advertisement

The skin-brain connection

The skin-brain connection involves various health disciplines including psychology, endocrinology (the study of hormones), skin inflammation, and others. While dermatology is the field of medicine that focuses on skin conditions, the term “psychodermatology” has arisen to reflect “the study of the connection between the mind and the skin.” In other words, it is the juncture of psychology and dermatology.

Advertisement

How stress influences skin problems

The skin is the main sensory organ for a wide range of external stressors, including heat, cold, pain, or other types of stress. Receptors in the skin transmit the outside signals to the spinal cord and then to the brain. The brain responds to these signals, influencing the stress response in the skin.

Stress exerts its effects on the skin primarily through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The skin acts as the outer boundary of the HPA axis in which hormones and their receptors are produced in skin cells.

Stress can trigger or aggravate various skin conditions such as psoriasis, acne, and dermatitis, among others, but it can also be a consequence of living with skin conditions, creating what can feel like a vicious cycle.

Advertisement

Psychodermatology in Canada

Sarah Allard-Puscas, founder of the Collaborative Group for Psychodermatology in Canada, which is the Canadian representative of the Association for Psychoneurocutaneous Medicine of North America, says, “Unfortunately, there are (currently) no psychodermatologists in Canada. Our group’s main goal is to implement it: psychodermatology aims to erase the border between the physical and psychological aspects of people struggling with a chronic cutaneous disorder.”

According to Allard-Puscas, the Collaborative Group for Psychodermatology in Canada also aims “to improve the quality of care and the quality of life of patients and to facilitate collaboration among dermatologists, psychiatrists, family physicians, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and any other health professional with a particular interest in psychodermatology.” As the group’s website states, “We are about treating the person with the skin condition, not just the skin condition.”

Advertisement

The importance of a holistic approach

The overlap of mental well-being and the health of the skin, and vice versa, provides a more holistic approach to skin care than simply treating skin conditions through pharmaceutical drugs and medicated creams. Instead, psychodermatology involves the use of psychotherapy. “Prescription drugs would be used sparingly, only in the event of need,” says Allard-Puscas.

“The main objectives of psychodermatology are to study the emotional impacts that the condition of a patient’s skin can create in order to help the patient overcome them and reduce the threats to well-being. The ultimate goal is to help the patient develop adaptive mechanisms they can use when a recurrence occurs,” says Allard-Puscas, adding that it’s “a multidisciplinary approach specifically adapted to each patient, emphasizing the improvement of the quality of life.”

The move toward a more holistic approach can have benefits for those suffering from skin conditions. Allard-Puscas adds, “The negative impacts of conditions such as psoriasis, acne, eczema, alopecia, and rosacea are not limited to the visible expression of the disease; they also cause significant emotional and mental distress.

“Through this subspecialty of dermatology, a biopsychosocial understanding of the context in which skin disease evolves can be achieved, offering patients new perspectives and an improved quality of life.”

As a result, psychodermatology may be helpful for a wide range of conditions, including acne, rosacea, dermatitis, hives, and others.

Spend time in nature

Research in the journal Frontiers in Psychology shows that as little as 10 minutes can boost mental health.

Practical tips to break the stress-skin cycle

Incorporate the following stress management practices into your daily life to help break the “troubled skin/troubled mood” cycle. These can include the following.

· Reduce the amount of sedentary time and incorporate moderate activity into your daily life.

· Speak with a mental health professional, friend, or family member; it may be helpful in releasing feelings of stress.

· Eat a healthy diet devoid of highly processed foods, which have been linked to mental health disorders.

· Avoid excessive use of alcohol and sugar; avoid drug use.

· Engage in self-care through activities such as reading a book, taking a bath, practising yoga and meditation, journalling, or participating in a favourite hobby.

· Get plenty of sleep; diffuse some essential oils such as geranium, lavender, orange, or vetiver to help improve sleep quality.

· Supplement with magnesium and a B-complex vitamin.

· Talk to your health care practitioner about a herbal formula to help reduce the effects of stress.

4 types of psychodermatological conditions

There are four classifications of health conditions in psychodermatology.

1. Psychophysiological disorders

These disorders include skin conditions that are frequently exacerbated, either in intensity or frequency, as a result of emotional stress. They include atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, acne vulgaris, lichen simplex chronicus, rosacea, and seborrheic dermatitis.

2. Primary psychiatric disorders

Primary disorders are skin lesions that are self-induced in the absence of a natural origin. They include neurotic excoriations, factitial dermatitis, trichotillomania, onychotillomania, and delusions of parasitosis.

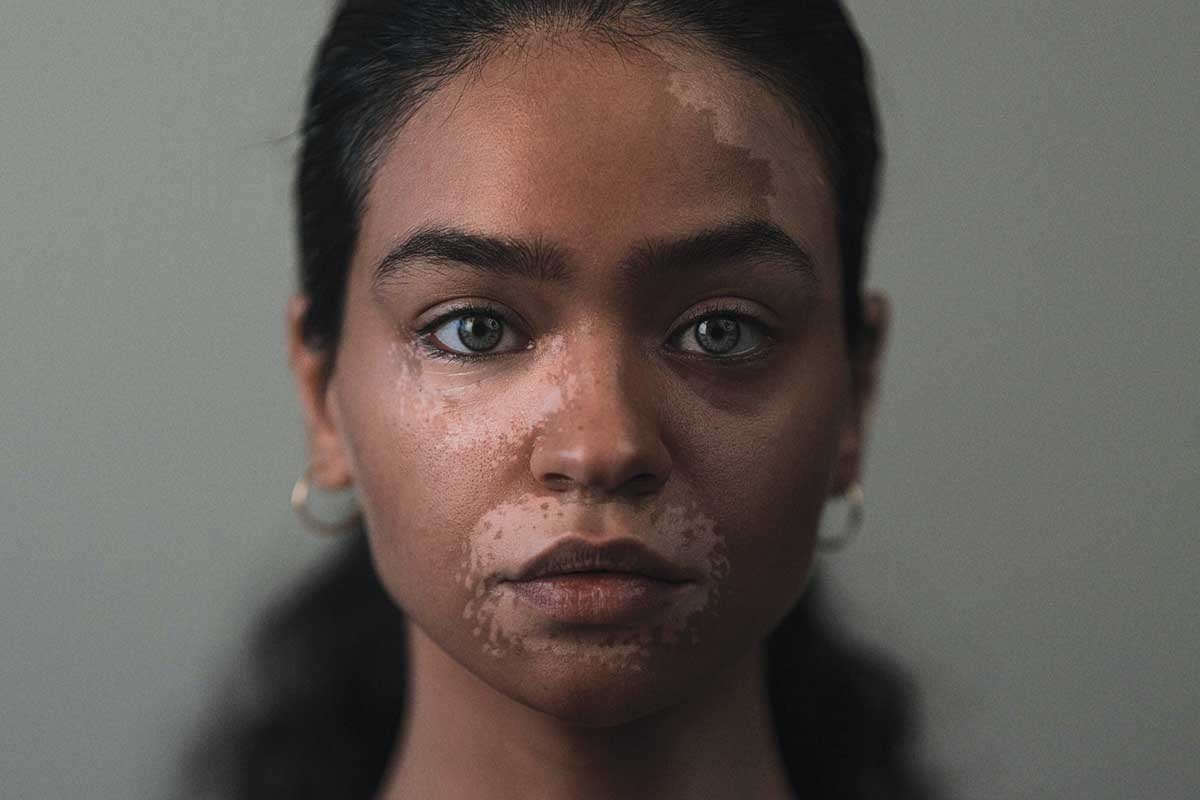

3. Secondary psychiatric disorders

Secondary disorders are psychological problems that develop secondary to the negative impact of skin diseases. In other words, a skin condition can have a profound impact on a person’s psychological welfare. These conditions include vitiligo and alopecia areata.

4. Cutaneous sensory disorders

These involve conditions in which the patient experiences abnormal sensations such as itching, burning, stinging, biting, or crawling on the skin in the absence of a diagnosable skin disorder. This includes glossodynia and vulvodynia, which are sensory disorders of the mouth or vulva, respectively. Psychiatric diagnoses may or may not exist, but if they do, they are typically anxiety or depression.

This article was originally published in the March 2024 issue of alive magazine.